The protocol and format explained!

(Updated June 5th 2021)

In my last post, I showed how cosign can be used to sign and verify container images today. In this post, I’ll explain how it works at each step of the way.

Life of a Cosign Signature

We’ll start with cosign generate-key-pair .

This command creates an ECDSA-P256 key pair (a private and a public key). The public key bytes are encoded in a PKIX formatted file. The public key looks like this:

— — -BEGIN PUBLIC KEY — — -MFkwEwYHKoZIzj0CAQYIKoZIzj0DAQcDQgAEroVS8KdYXp5SSI5YDwwQymSByQAM7MDgk9po3wpp/hHZAzCLsu+j3axrJJ5nMet9tqX1eH8yk21G626Z8lrkQA==— — -END PUBLIC KEY — — -

The private key is marshaled into PKCS8 formatted bytes which are then encrypted using a nacl/secretbox and passphrase using scrypt for the KDF, and written to disk in a PEM file with the header: BEGIN ENCRYPTED COSIGN PRIVATE KEY. A private key looks like this:

— — -BEGIN ENCRYPTED COSIGN PRIVATE KEY — — -eyJrZGYiOnsibmFtZSI6InNjcnlwdCIsInBhcmFtcyI6eyJOIjozMjc2OCwiciI6OCwicCI6MX0sInNhbHQiOiJrSGE5Q1ozTzdFSUtubTNWbnh2WVdvY2k2RWNhcEFDZE9NbWxXRTV4YTY0PSJ9LCJjaXBoZXIiOnsibmFtZSI6Im5hY2wvc2VjcmV0Ym94Iiwibm9uY2UiOiJXcUxtcHZJaml5SklmWGt4YnJaUStXUzg3dFlBeUY1SiJ9LCJjaXBoZXJ0ZXh0IjoiR1BXMjB3Q1l6d09PeUt2aDMwUzFudnFmLyt0ZVBYSmtXM3F3TzFEMmwrdk1GQ3o2MHFKU1I1ZTF1UTRlcWxUaTdmdjNkYVlLcUJyNlltcnFGV1YxcnlDQ2gwMXhzOGFsd3BxSS85U0pTTjNVVnZXODkxc1hESHc2SEo5dkNIZHdNUldvWHVVTUdZb0FDd2dyUWZiK3lGNnFOYkQ3dEkrdExlWjRSb1owa3R3Q24zQVErd2hjU0h4ZjYvQmFNVUwzK1gyK3dnNENVM1dtb0E9PSJ9— — -END ENCRYPTED COSIGN PRIVATE KEY — — -

Cosign sign

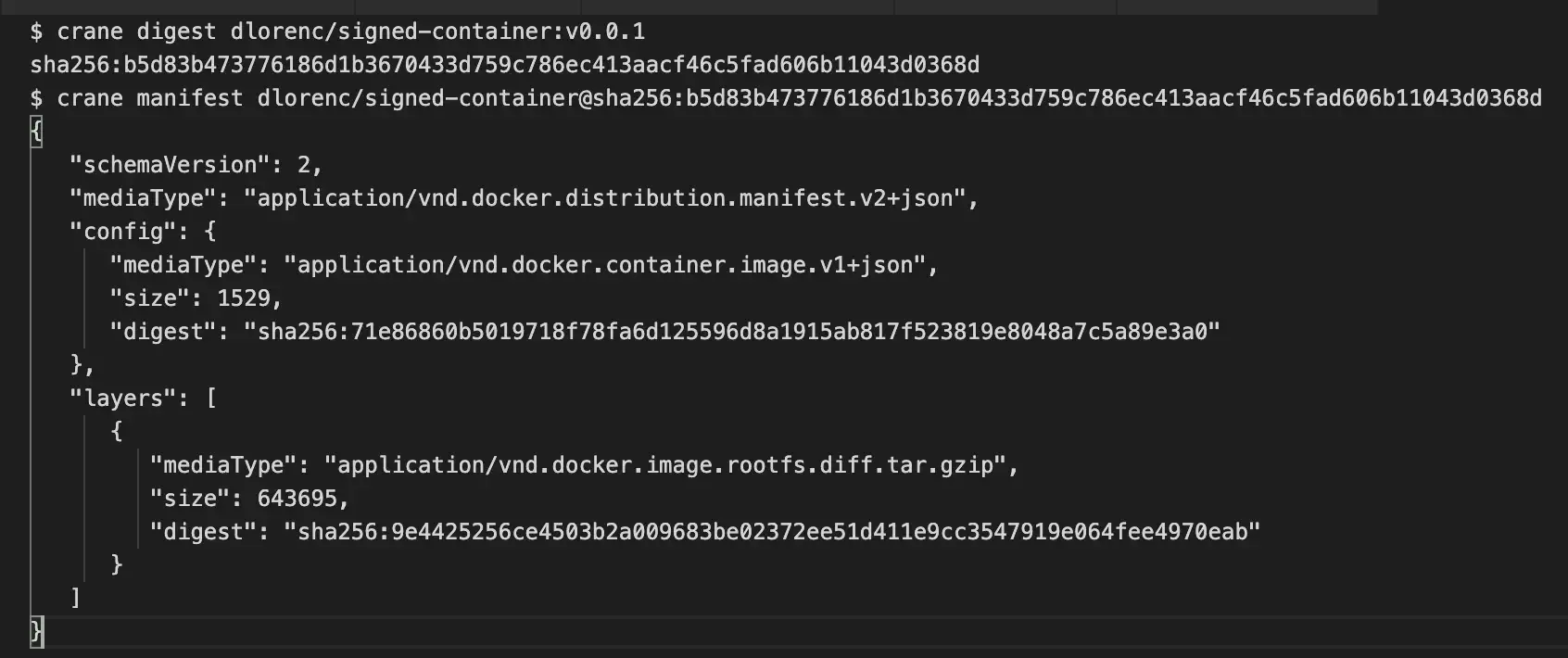

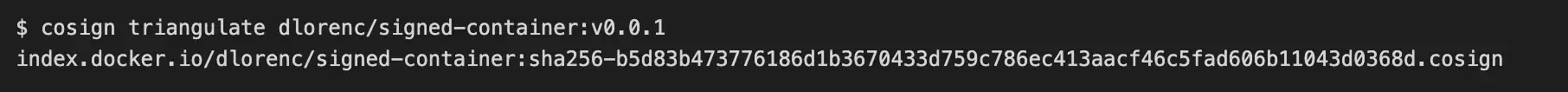

Next, we sign a container image with: cosign sign -key cosign.key <image>. First, cosign needs to know where to store the signature. To do this, cosign fetches metadata about the referenced image, including the digest. Cosign currently uses a fixed naming convention to decide the name for a separate image, at which we can store the signature. This can be shown with cosign triangulate:

$ cosign triangulate dlorenc/signed-container:v0.0.1index.docker.io/dlorenc/signed-container:sha256-b5d83b473776186d1b3670433d759c786ec413aacf46c5fad606b11043d0368d.cosign

The Payload

Now that we have the location and metadata, we can generate the signature. An image is a “virtual” concept. There is no canonical “on-disk” object that can be signed over. There is however — a canonically-structured distribution object — that can be signed over. This object is the OCI’s Image Manifest. These are JSON manifests referencing all of the contents of an image (metadata, file system layers and configuration).

This JSON is canonically-encoded and sha256-hashed, giving us a canonical digest that can be signed over. These digests are commonly used to reference images by digest in registries, using the @sha256:<abc123> format. You can see one using the amazing crane tool, available here:

So we have a subject to sign: the sha256 digest of the container image. We could simply sign that and be done. But someone said, why not add a few more fields for metadata first!

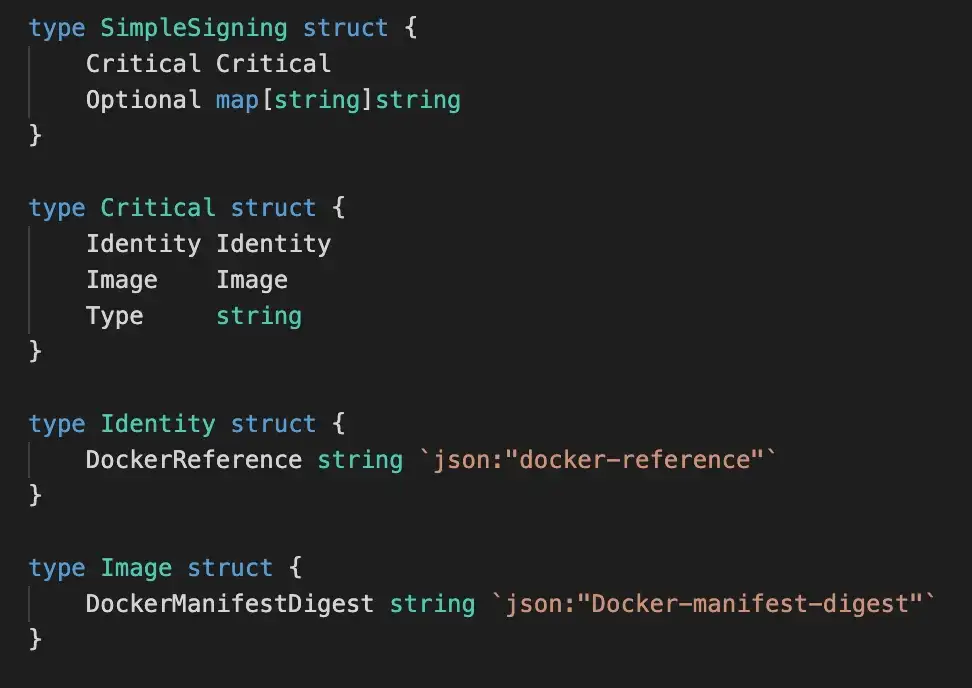

Cosign implements the Red Hat Simple Signing spec, defined here. In Go, it looks like this:

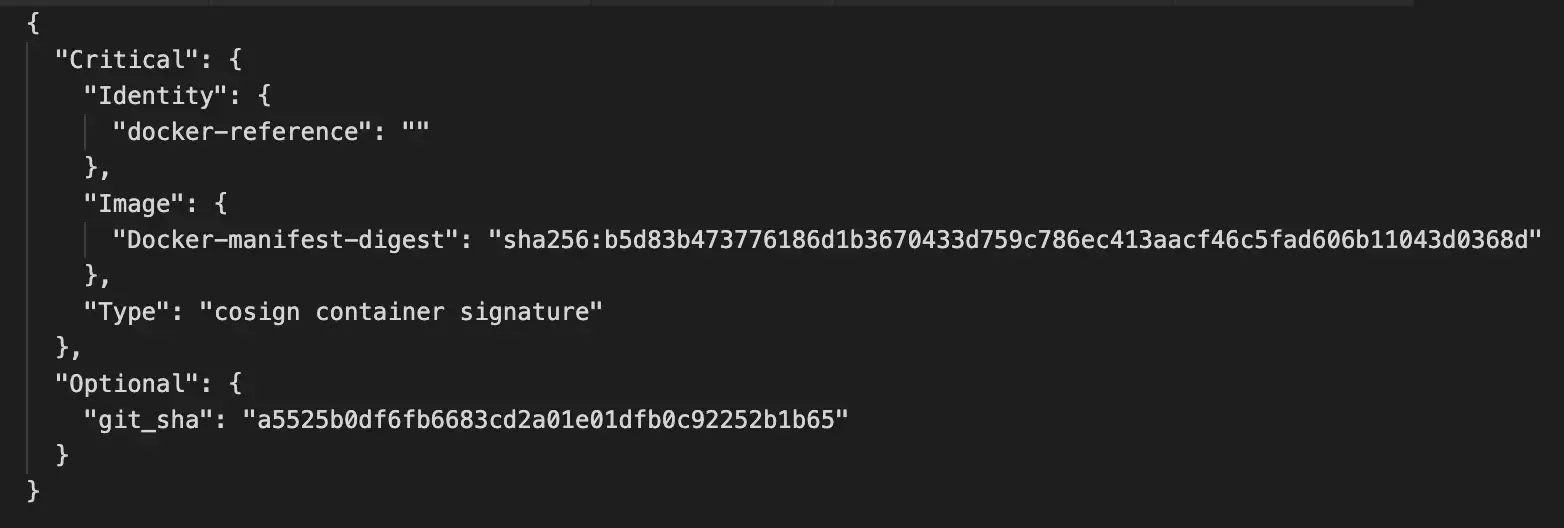

In JSON:

The Signature

We decrypt our private key, using the passphrase, KDF and decryption mechanism from above. We use this key to sign the payload and get a signature. The signature is then base64 encoded for storage.

We have the storage location from the first step:

We can’t just write a blob to the registry’s CAS — that would get garbage collected with nothing referencing it. So we have to craft an object (to hold the signature) we can store there. There are two options here: Manifest Lists or Image Manifests. We use Image Manifests (specifically the OCI Media Type). OCI Artifacts would also work, but are really just a specific type of Media Type on the standard OCI Image Manifest with limited registry support.

Multiple signatures may be attached to a single image, so we have to store multiple signatures in this same object. We could store multiple objects and page through them, but registry support for listing is basically non-existent. There’s a proposal to make listing consistent somewhere too…

Registries only support CRUD operations on objects, so we must download the existing image data, mutate /append to it, and write it back. This is racy, last-write wins. There’s an OCI distribution proposal in process to allow optimistic concurrency through HTTP ETags that will help here.

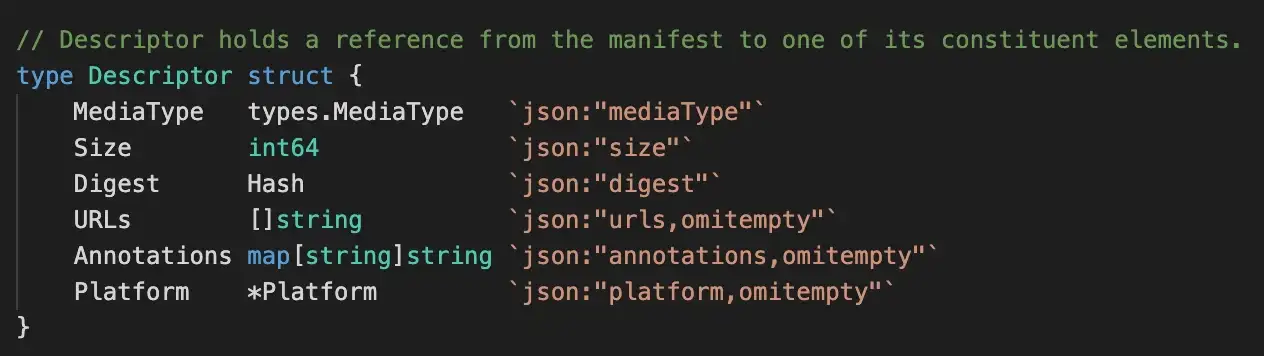

So we download the manifest and append a layer object (an OCI Descriptor object) to the image. An OCI Descriptor is a basic structure to reference another object. It looks like this, in Go:

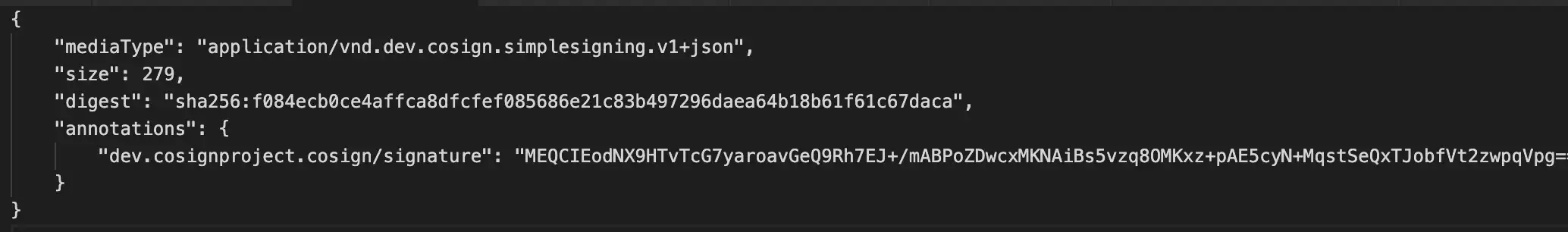

And like this, in JSON:

We set an annotation with our media type as a key, and the signature base64-encoded. The layer body itself is stored in an OCI Blob which is referenced by the digest field in the Descriptor. There’s another ongoing proposal in the OCI Distribution group to allow storing in-line data in a Descriptor. This would allow us to skip a round-trip to the client during verify, by placing the payload data in the Descriptor rather than as a separate blob.

The Verify

This works similar to above, but backwards. We start by parsing the public key from disk. It is PEM-Decoded, PKIX-encoded file, so we reverse that. We then fetch the signature(s) object from the location using our resolution scheme defined above. We resolve the tag to a fixed digest. This is Important.

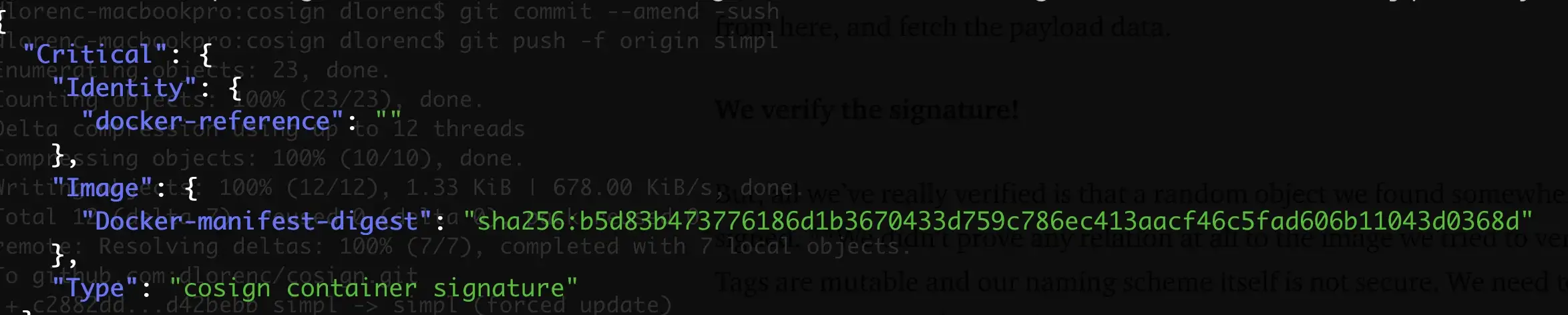

Next, we iterate through the layers where signatures are appended to. We filter for layer objects (Descriptors) that have an annotation matching our key type dev.sigstore.cosign/signature. We decode the signature from here, and fetch the payload data.

We verify the signature!

But, all we’ve really verified is that a random object we found somewhere was signed. *We didn’t prove any relation at all to the image we tried to verify!*. Tags are mutable and our naming scheme itself is not secure. We need to inspect the payload we took such care to create earlier.

In particular, we look at the Critical.Image.Docker-manifest-digest field:

The value here MUST match the value of the digest of the image we fetched at the start of this process. Once that check is complete, we can now prove that the signature payload was “attached” by reference to the original container image that was signed.

Cosign supports extra features to append keys and values to the “Optional” section of the Payload with the -a flag. Cosign also supports simple, predictable verification logic/filtering on these key-value pairs, with the same -a flag.

Summary

This approach is simple (basic naming-scheme) and works across most registries (every one I tested except for Quay. There are a few downsides, such as the racy-ness of writes, and the lack of garbage-collection of signatures. Client-side support to copy related objects across registries is not automatic, but would be simple.

The naming scheme is needed because registries do not support a way to “attach” objects to each other with reverse indices. An object can directly reference another (Manifests reference blobs viaDescriptors), but that reference mutates the Manifest. From a Manifest you can find the Blobs via Descriptors, but from a Blob you cannot find theDescriptor or Manifest.

Other approaches such as embedding the signature in the Manifest itself would similarly mutate the Manifest by modifying it. This technique could work, but is generally deemed undesirable because it would break most deployment workflows — which assumes most images are pinned by Digest, as soon as the image is built. Signatures are added later throughout the pipeline.

The cosign signature storage format and Payload scheme are as simple and widely supported as they could be. I don’t love either one. I’m really not picky, but the Simple Signing format is kind of quirky. The-caSiNg is pretty strange, the names are incorrect (Docker-manifest, for OCI stuff?), but it has all the right fields. One option would be the OCI Descriptor I mentioned before. I opened a proposal for that here in the Notary V2 organization.

I hope we can get direct support for the linking in the OCI specs to fix the racy-ness and garbage-collection issues. I’ll be actively following the OCI discussion and pushing for better support so we can hopefully converge eventually. If you’re interested in following along, this might be the best issue. But if you care about broad support and want something soon, cosign works as well as about anything I can see coming in the next 6+ months.

Please feel free to reach out! Cosign is developed as part of the sigstore project. Join us on GitHub or Slack! I’m also happy to help you get started, feel free to reach out on Twitter!