Disclaimer: The following is representative of the authors views, and not necessarily that of the sigstore community.

OpenPubKey was announced October 4th by Docker and BastionZero as a new Linux Foundation project. It’s a new scheme for using OIDC providers to sign arbitrary objects. It bears a lot of resemblance to Sigstore, so I thought it would be worth taking some time to explain the differences, including some advantages and disadvantages.

The major difference between OpenPubKey and Sigstore is that OpenPubKey eliminates the centralized, server-side components of Sigstore, namely the Transparency Log and Certificate Authority components. In this sense, it appears much simpler to use and operate. These systems are actually somewhat load-bearing in the Sigstore architecture, so they can’t simply be removed without some tradeoffs. It’s entirely possible these tradeoffs make sense for certain architectures, but they weren’t really discussed in the OpenPubKey paper so it’s hard to understand if they were considered. We did consider this architecture in Sigstore though, so I can explain why we didn’t feel it made sense for generic artifact signing.

There are two main issues with the elimination of the Certificate Authority and Transparency Log (Fulcio and Rekor, respectively) - 1) publishing raw identity tokens (JWTs) introduces several privacy concerns with tracking identities over long periods of time, and across renames, and 2), relying directly on OIDC signing keys for verification introduces a large amount of complexity (and attack surface) on clients, who have to handle the key rotation aspects of OIDC providers.

Let’s start with some background on how OIDC works, how Sigstore works, how OpenPubKey works, and then how it all fits together and where these problems come in.

How Sigstore Works

The Sigstore architecture is admittedly complex! Complexity is bad and should be avoided where possible. Unfortunately in this case, we believe the complexity here is necessary. Fortunately, it can be encapsulated into some very useful tools and programs that hide this complexity to provide a great user experience.

The “keyless” flow works roughly like this:

- A user logs into their identity provider (google, github, microsoft, etc.).

- The user requests an “identity token” from this provider, that they can use to assert their identity to a third party.

- The identity provider checks that they are who they say they are (this method is up to the provider), and then it gives the user that token.

- The user hands that token to Fulcio

- Fulcio has a trust relationship with the identity providers (Google, Github, Microsoft, etc.), and can verify that the token was correctly signed by these providers. Fulcio then knows that the user is who they say they are, as vouched for by the specific identity provider.

- Fulcio hands the user back a signed x509 code signing certificate that the user can use to sign code or other artifacts with. This certificate contains claims that are bound to the original ID token (without containing every field), preserving the trust chain.

- The user signs their code or other artifacts, and attaches this certificate alongside the signature.

When someone wants to verify the signature:

- They verify that the code signing certificate was signed correctly by Fulcio

- They verify the identity and issuer of the certificate match the identity and issuer they expect.

- They verify the signature against the artifact.

- At this point, they know that the identity in the certificate signed the artifact, as vouched for by Fulcio (who checked the identity from the identity provider).

Note that the “keyless” flow in sigstore is optional, many other flows exist and are also supported, and these other flows may be better in some cases! The keyless flow is most comparable to that of OpenPubKey, so that’s what I’m explaining here.

This whole process sounds complex, and it is! The user experience is very simple though, the entire process can be wrapped up into two commands:

$ cosign sign

$ cosign verify

Also note that this is still a simplified view. There are a few other things going on here with transparency logs that you don’t need to understand quite yet.

How OpenPubKey Works

In OpenPubKey, the user goes through a similar, albeit simpler flow:

- A user logs into their identity provider (Google, Github, Microsoft, etc.).

- The user requests an “identity token” from this provider, that they can use to assert their identity to a third party. DIFFERENCE ALERT As part of this step, the user embeds some information into the ‘nonce’ field of the request. This is an implementation detail of the OIDC protocol. (more on this below).

- The identity provider hands back the signed token, including the signed nonce, which contains that special information.

- The user then uses this token directly as a certificate - the nonce field contains information about the user’s signing key, so it binds their identity to that key so they can sign artifacts right away!

- The user attaches this token alongside the signature, similar to a certificate.

For verification:

- They verify that the identity token was signed by the identity provider (Google, GitHub, etc.)

- They verify the signature against the artifact

- At this point, they know that the identity in the certificate signed the artifact, as vouched for by the identity provider

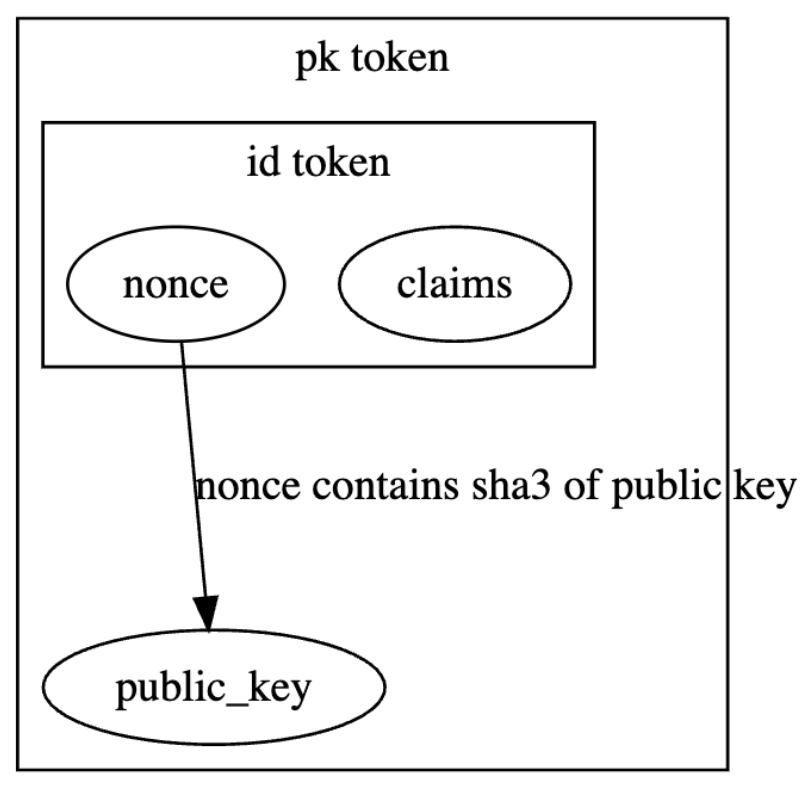

This explanation is a bit over-simplified. OpenPubKey actually uses two tokens (the original ID token which contains the nonce, and their own PK token which effectively wraps the ID token and contains the public key. The full setup looks like this:

OpenPubKey also contains support for expiration - the default in this mode is for these certificates to be valid for two weeks. The paper doesn’t really specify what happens after that, or how to handle revocation, but we can imagine ways these can be constructed on top of this protocol.

This effectively removes the OIDC part of Fulcio (but not its transparency log) by using the token directly as a certificate. (Also the transparency logs I mentioned earlier, but hold on for that part). The use of the nonce is a clever hack (and I mean that in the best way possible!), but it introduces another problem:

OIDC identity providers were designed to produce tokens that can be verified in very close succession to the time they’re signed.

When you login with Google to a third-party website, Google issues the token and you hand it right to the website. Signed artifacts might need to be verified hours, days, months, or years later. Identity providers rely on this short-term nature by rotating their keys frequently. Signing keys are typically rotated hourly or daily by most major identity providers, and there is no way for external observers to verify that an older signing key was ever authentic.

That means when you get to step 1 in the verification process:

- They verify that the identity token was signed by the identity provider (Google, GitHub, etc.)

You might run into trouble if you’re verifying this signature much later than it was generated. The paper acknowledges this problem and mentions that clients will need to constantly monitor the keysets used by identity providers and store them all locally.

Additionally, providers make no guarantee that the keys they used for signing are still protected and private after they’ve been rotated out. I’m not aware of anyone doing this today, but providers are completely within their rights to publish private signing keys after they’re rotated out. This sounds silly, but it comes up regularly in discussions around DKIM and other signing keys. Relying on the secrecy of a signing key outside the window the provider guarantees that secrecy is another potential recipe for disaster!

Quick Nonce Aside

We glossed over the nonce hack above, if you’re curious for more information on how it works, here you go! If you’re already familiar with certificates and OIDC, you can probably skip this part.

Certificates

A certificate sounds complicated and intimidating, and all the nomenclature around x509 and PEM and DER encodings don’t help. But at their core, certificates are actually pretty simple. I love this blog from SmallStep as a full primer on how they all work. It says that a certificate binds an identity to a public key. You can do this with x509 and CAs and openssl, or you can just make a plain text file that says:

Identity: My name

Public Key: <some public key encoded as text>

This is a perfectly valid certificate too! No one will know what to do with it, but most people don’t know what to do with x509 certificates either.

Semantically, this certificate says that the public key contained in that certificate is owned by the identity, also contained in that certificate. To trust that data, you’d either have to directly obtain that certificate from someone you trust, or make sure that it’s been cryptographically signed by someone you trust. Most systems work with signed certificates, from something called a certificate authority (CA).

Following this definition, anything that contains an identity and a public key that’s signed by something you trust can be used as a certificate. Most certificates come from well-known CAs that speak the x509 protocol, but other protocols exist. SSH keys can also be signed by SSH CAs, for example. The nonce hack makes clever use of this fact, by getting an OIDC provider to act as a trusted system, and “tricking” that into signing something that contains a public key and an identity.

OIDC

For the second half of the nonce hack, we have to dig into the OIDC protocol a little bit. I would definitely not recommend reading the entire OIDC RFC under any circumstances, but here it is just in case you’re feeling especially masochistic. This meme is a much better, albeit less thorough explanation of the protocol:

Users authenticate to their Identity Provider somehow. This is up to the identity provider, but usually you just login with your browser. After that, you request an Identity Token over a standardized API. This Identity Token can be handed to a third party (called a Relying Party in OIDC-speak) to prove you are who you say you are.

Identity Tokens are signed by the Identity Provider, and contain a bunch of fields specified by the OIDC protocol. One security goal of the protocol is that the API for requesting tokens should be resistant to replay attacks - that means someone that intercepts one of these requests shouldn’t be able to consistently replay that same request to keep getting new tokens. This is implemented using something called a nonce - the request is supposed to include a random-ish value in it, which makes its way into the signed token. The application verifies the nonce in the token matches the nonce in the initial request, and can then be sure the token was unique to that request. The protocol is flexible in what actually goes into that nonce value, it’s just supposed to be unique across requests.

The Nonce Hack!

Careful readers might be able to spot the hack now! There’s a field you can include whatever you want in that will be signed by someone you trust in the response! If we embed a public key and an identity in there, we can squint and call that a certificate! We can even include some random data to preserve the replay-resistance property of the protocol.

Tradeoff #1 - Server-Side vs. Client-Side Complexity

This is the first tradeoff, OpenPubKey eliminates some server side complexity - no one needs to run a certificate authority (Fulcio), but clients need to perpetually track all the signing keys used by all identity providers to verify historical signatures. If you start tracking them today, you can’t verify signatures generated earlier than today. If you miss one because your system goes down, you might not be able to verify an authentic signature.

There are ways around this - someone could run a central log of public keys over time. The current OpenPubKey reference implementation contains a TODO with just that - fetch the keys from some log somewhere. Someone could maintain and then publish this for everyone else to use and trust, but at this point you’re trusting the maintainer of that list, not the original Identity Provider. This bears repeating - after a key has been rotated out from an Identity Provider - you have no strong guarantee that the key was ever actually used by that provider. If you obtain the historical key set from anyone else, you are effectively shifting all trust of those historical keys to that third-party.

There are fancy protocols like Merkle trees and transparency logs that can be used to make sure users can actually trust that the data in this system hasn’t been tampered with, but these can’t actually ensure the data was correct to begin with (it’s the key-owners responsibility). To state this strongly, one more time, this protocol as designed cannot handle historical verification (signatures produced several days ago or more) without introducing blind trust on a third party.

I can imagine some transparency log architectures that can help make this trust slightly less blind, but they’re not trivial to design or roll out. You’ve reintroduced the server-side complexity and third-party trust that OpenPubKey was designed to eliminate! Also, this is basically equivalent to the Sigstore architecture, this is exactly where those transparency logs I mentioned earlier come in.

There might be cases where clients want to or need to assume this complexity. It makes sense in certain environments! I don’t think the paper really does this tradeoff justice though, it’s a bit glossed over and left “as an exercise for the reader”.

By operating in a stateless mode, signers have no way of detecting key leakages, or other signers trying to impersonate them. Sigstore offers both a CT log, and an artifact signature transparency log, which signers can monitor for adversary activity.

Tradeoff #2 - Potential Privacy Issues Caused By Reusing the Identity Token instead of Using a New Certificate

The second tradeoff is again a case of simplicity vs. complexity - the OpenPubKey flow uses the raw JWT OIDC token as the certificate, by using the nonce field to bind the token to the signing key. This is certainly simpler than using another service to generate a new object (the x509 certificate), but it comes at a cost - JWTs weren’t meant to be used this way! They were designed for users to fetch from a trusted service and hand to another trusted service, not to publish on the internet. This means they might (and in practice, probably do) contain information you might not want to disclose.

Identity providers can (and do) embed lots of information in these tokens, and they’re signed as an entire entity. You can’t remove or obfuscate any of the information in this token without invalidating the signature (which is the entire point of using it directly). These fields usually consist of things like iss, sub, aud, exp, and iat, which are required to make the scheme work, but as you can see in this example they might contain things like “name”. Sigstore allows users to sign under any identity they want (typically an email address, but not always), and strips out any extra fields from the token as part of issuing the certificate. If the name is included in the token, sigstore sees it, but sigstore doesn’t pass it on to the certificate issued by Fulcio, so users verifying the signature have only the information they need.

This isn’t just a privacy issue, ID tokens are commonly treated as bearer tokens for authentication systems. Passing them around externally can pose a security risk! Relying parties are supposed to verify claims within the token to ensure the token received was generated specifically for that use case (so an ID Token for OpenPubKey shouldn’t be accepted to log into a social network), but that relies on the relying party to properly verify those claims, and security incidents due to improper claim verification happen regularly. The OpenPubKey implementation (not the paper) has an issue and a potential workaround to this by using zero-knowledge proofs - it looks promising but I’m not enough of an expert to know if it will work out.

Wrapping Up

I believe the OpenPubKey approach is clever and might solve some use-cases that Sigstore doesn’t solve well. I’m admittedly biased, having participated deeply in the design and implementation of Sigstore, but I believe these tradeoffs (the potential privacy leak of information contained in the identity Tokens, and the large amount of complexity for expired key management pushed to all clients) favor Sigstore for most supply chain security use-cases.

The added complexity of using a central certificate authority has been mostly mitigated by the excellent efforts of the Sigstore community and sponsoring companies, including Stacklok, Chainguard, Google, Red Hat, Purdue University, and GitHub. The service exists and takes a ton of work to keep running, but the community does the hard work, so users don’t need to.

I think it’s worth pointing out these two trade-offs, so users can make informed decisions on which approach they want to use! There’s no free lunch here, and eliminating those components introduces a large burden on clients that will be tricky to get right, and can pose large security consequences if they’re done wrong.

I don’t know if the OpenPubKey maintainers considered these tradeoffs because they’re not discussed in the paper. I do know that we discussed these and made the tradeoffs intentionally as part of the Sigstore design. If anyone does try to roll this out at scale, I look forward to seeing how they mitigate the complexities outlined above, especially in client-side verification. It’s also worth noting that a very similar scheme to this one was proposed earlier this year, called “How to Use Sigstore Without Sigstore”. Zack Newman published an excellent blog post explaining the tradeoffs in that design as well, it’s worth a read for anyone that’s trying to understand OpenPubKey and Sigstore as well!

Acknowledgements

I’d love to thank Fredrik Skogman, Hayden Blauzvern, and Dan Luhring for their thorough reviews!